Cigarette smoking in the 1950s - USA

Beating the cancer scare

Just before Christmas 1952, millions of Americans read that cigarette smoking caused cancer. [1] In 1953 cigarette sales fell for the first time since the Great Depression. Americans were cutting down and giving up. However, by the end of the decade they were smoking more cigarettes than ever. How did big tobacco beat the cancer scare?

The cancer scare

Before 1950 there was a lingering suspicion about cigarettes and health. Most people knew that they could give you a cough or a dry throat. There were conditions such as "smoker's heart" which could be a cause of death but there was no real evidence linking cigarettes to any specific illness.

R J Reynolds, the makers of Camels, America's number one cigarette, reassured the American public that "More doctors smoke Camels than any other cigarette".

At the same time the medical profession was aware of an alarming increase in lung cancer rates in both Britain and America. Two statistical studies, carried out in the UK by Bradford Hill and Richard Doll, and the US by Ernst Wynder and Evarts Graham, named cigarettes as the cause.

Doll was a smoker but his own research convinced him to give up. Graham was the surgeon who performed the first successful removal of a cancerous lung in 1933. He was a heavy smoker himself and did not believe smoking was the cause of lung cancer. He was persuaded by his enthusiastic student Wynder, who, with Graham, published the first statistical paper linking smoking and cancer a couple of months before Doll and Hill's definitive study published in December 1950. Graham died of lung cancer six years later.

Both reports were published in scientific and medical journals, not the sort of thing the average American would flick through in their lunch hour. However, in 1952 Reader's Digest, a weekly read by millions, published an article called 'Cancer by the Carton' by the journalist Roy Norr. [1] Norr was a veteran anti-tobacco campaigner of religious zeal. He had condemned cigarettes before, but now had some real evidence to put before the public.

[Chart 1] Cigarette sales by year, 1950s (billions of cigarettes). The graph shows a drop around 1953-4 but a recovery by the end of the decade. Had the cancer risk gone away?

The statistical evidence was compelling but epidemiology (statistics for medical research) was a new branch of science at the time. Some questioned its validity. There was a correlation between smoking and developing lung cancer, but could there be some other reason link?

American smokers were further worried by the publication in 1953 of the results of scientific experiments which claimed to show cancer could be induced in mice by painting them with cigarette tars.

America starts to quit

Cigarette smoking is hard to give up. The knowledge that it is bad for your health is not enough. However, in 1953, many Americans were prepared to do just that and cigarette sales fell for the first time since the Great Depression. More still quit in 1954. [2]

What the industry needed, and the American public would have loved, was a safe cigarette. People could then carry on smoking without guilt. The tobacco industry could carry on earning huge profits.

Enter the filter

What if a device could be found that removed the cancer-causing chemicals from cigarette smoke? The American public could carry on smoking without worrying about their health.

Such a device might have already existed. In 1925 Hungarian inventor, Boris Aivaz, patented a cigarette filter made from crepe paper. Several manufacturers took up the idea but the most successful brand with a filter was Du Maurier, launched in the UK in 1929.

In those days, filters had nothing to do with filtering anything out of the smoke. Their main purpose was to stop tobacco bits from getting into your mouth. These early filters were less effective at filtering tar and nicotine than the tobacco they displaced.

Filters were especially popular with women. Men saw filters as feminine. Du Maurier was a posh cigarette which appealed strongly to wealthy women smokers. It had its own unique hinged box and an Art Deco design.

In 1950 three filter brands were on general sale in the US; Du Maurier was one. The other two were home grown. Parliament, America's first filter cigarette, was introduced by the American Benson & Hedges firm in 1931. Parliament, like Du Maurier, was an expensive cigarette, priced well outside the popular market. The third, Viceroy, was priced at the popular level.

Could filters be the answer to the cancer scare?

The problem was a complex one. No-one knew what in cigarette smoke caused cancer. Studies found that cigarette smoking and lung cancer were statistically related but which compound was responsible? Was there anything that the filter could filter out that would allow people to carry on smoking without worry? At the time this seemed a reasonable question to ask. With hindsight, the search was futile.

So what should the filter filter out? The two main elements to cigarette smoke are tar and nicotine. Nicotine was known to be a poison if taken in sufficient quantities, could this be the carcinogen? Tar is the mixture of compounds that are the result of burning tobacco. If manufacturers could make a cigarette that delivered less tar and nicotine, would this be enough? After all, statistical evidence showed that heavier smokers took a higher risk, so could filter cigarettes reduce this risk to an acceptable level?

[Chart 2] Cigarette sales by type in the 1950s. This graph shows the start of a decline in cigarette sales but filter sales expand at a rapid rate reversing the decline.

Before the statistical evidence linking cigarettes and cancer was widely publicised, research director at P Lorillard, Dr Harris B Parmele, was working on a safer cigarette. Parmele was a biologist by training and was used to leafing through obscure scientific journals. He thought he had come across the ideal cigarette filter when he read declassified military research about an effective gas mask. [3]

This research turned up a mineral which Parmele believed could be used as a cigarette filter. This mineral was also used in the filtration systems for atomic power plants and for air purification in hospital operating theatres, two facts Lorillard's ad men would make much of in the coming years.

In tests the new material was impressive at removing tar and nicotine from cigarette smoke. So much so it had to be tweaked to let any smoke through. The patented technology was given a trade name, the Micronite filter. The new cigarette brand was to be Kent, the name of Lorillard's Chairman. His signature appeared on every pack.

Lorillard's marketing men were very careful not to imply cigarettes were bad for everyone. The target market for the new cigarettes was "sensitive smokers". According to the company's advertising:

"Published medical reports have shown that at least one out of every three smokers is sensitive to the tars and nicotine in tobacco."

How would you know if you were sensitive? It was a question that remained unanswered.

The adverts correctly claimed Kent's filter removed seven times more nicotine and tars than other filter cigarettes. Kent had some early success but failed to capture a big market share. Kent's problem was that it filtered too well. [3]

Frank Mosher, a Ford dealer from Montana, California wrote to Readers' Digest in 1958. He explained to the Editor that he switched from Camels to Kent after reading an article in the magazine which showed Kent had the lowest tar and nicotine of all cigarette brands. Whilst he smoked a pack of Camels a day, he found he had finished his first pack Kents by the time he came home from work. [4]

There were other ways of compensating for low tar. Each cigarette is not smoked equally. Before Kent first went on sale, Parmele discovered from test trials that smokers drew harder on Kent cigarettes to get more flavour out of them and more nicotine.

Letting the flavour through

Although Lorillard failed to capture a significant market share with Kent, sales of other filter brands skyrocketed in the early 1950s. Sales of the top three cigarettes Camel, Lucky Strike and Chesterfield were tumbling. The big three tobacco firms, American Tobacco (Lucky Strike), R J Reynolds (Camels) and Liggett & Myers (Chesterfield) were not going to be left out.

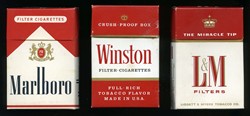

A rash of new filter brands followed in the wake of Kent. Liggett & Myers was next, with L&M in 1953. 1954 was a big year for new filter brands. R J Reynolds launched Winston, American Tobacco introduced a filter version of Herbert Tareyton and smaller firm, Philip Morris, rebranded Marlboro as filter cigarette which appealed to men.

The cigarette that won the 1950s' filter war was Winston. Winston was launched as the filter cigarette that was easy to draw, with its well-known slogan "Winston tastes good, like a cigarette should".

The driving force behind Winston was a salesman, not a scientist. Although Reynolds President, Ed Darr, first saw filters on a trip to Switzerland, it was Sales Manager, Bowman Gray who decided that the time was right for Reynolds to introduce a filter cigarette in 1954. [5]

Gray was the son of the former Reynolds Chairman, also called Bowman Gray. In spite of his privileged background, he put in plenty of hours and shoe-leather as a traveller for Reynolds. Gray was an enthusiastic smoker who had a nose for a good blend of tobacco. He supervised the blending and final selection of Winston, as well as participating in the brainstorming session that came up with the slogan "Winston tastes good, like a cigarette should".

How did Reynolds succeed where Lorillard failed? In preparation for their own entry into the filter market, researchers at Philip Morris examined Winston cigarettes in detail. They found that the Winston cigarette had a filter made of the same cellulose acetate material used by both L&M and by Viceroy. However, the Winston filter was different, it let through more tar and nicotine; it was less effective.

According to an inter-office memo sent to the Philip Morris Chairman, Joseph F Cullman, in 1954, the Winston filter was "the least efficient filter" compared to Parliament, Ligget & Myers (L&M), Kent and Viceroy.

Winston was not a Camel with a filter. It was a different blend, a blend of stronger, cheaper tobaccos. Winston delivered more tar but slightly less nicotine than Camel. So smoking a Winston was no better for you than smoking a Camel.

R J Reynolds was by no means the only firm to do this. Tobacco growers in the mid-fifties were dismayed that once prized milder grades of tobacco leaf were being spurned by cigarette makers in favour of a stronger leaf that had previously been unsuitable for cigarettes.

Cigarette makers had found that filters sold, because of the health angle. A market survey for Lorillard showed that 83% of smokers thought that filter cigarettes were less harmful than unfiltered. However, they also found that smokers rejected filter brands that did not have the same flavour and satisfaction as regular cigarettes. So they responded with filter cigarettes which were little better in terms of tar and nicotine content than the plain cigarettes they replaced.

Did they deliberately mislead? Cigarette makers claimed they were responding to customer demand, without worrying too much about what was driving that demand.

Advertising copy talked about removing tar and nicotine, the Tar Wars had begun. The copy stopped short of telling customers that cigarettes were safe. If you wanted to believe, and many smokers did, it gave you reason to.

"Only L&M filters give you the Miracle Tip - the effective filtration you need. You get much more flavour, much less nicotine - a light and mild smoke. Remember it's the filter that counts ... and L&M has the best!" L&M

"Along with finer flavour you get Winston's finer filter. It's unique, it works so effectively" Winston

"The Marlboro exclusive Selectrate Filter is made of finely spun filaments of pure white cellulose acetate. This is the modern effective material for filter cigarettes. And Marlboro isn't stingy with it" Marlboro

The advertisers were careful not to say very much. What were the filters supposed to be effective against? Although there were few restrictions on advertising claims in the 1950s, the FTC (Federal Trade Commission) did try to stamp out completely unsubstantiated claims. Charles Grandey, Director of the Commission, picked up Liggett and Myers on some of their advertising copy for L&M. He objected to the word 'assurance' that was in some of their advertisements, as it gave smokers false assurance. He also objected to their claim that the L&M filter was the best; L&M had the fourth highest tar and nicotine content in the industry.

[Chart 3] Average tar content by cigarette type, filter kings v regulars. The comparsion is with the most popular size of each type (figures from Consumer Reports, January 1960, page 21)

The cigarette makers were very coy about how much nicotine and tar these filter cigarettes delivered, although they often trumpeted how much they took out. America's CU (Consumers' Union) magazine came to the rescue, publishing regular tar and nicotine tables. They also found that the cigarette makers played around with the tobacco blends and filters, tuning them precisely to suit their marketing needs.

[Chart 3] Shows that the tar content of filters rose between 1955 and 1957, but fell dramatically after 1957. The chart also shows that there was very little difference between an average filter cigarette and an average regular one.

False and misleading

The claims made by the tobacco firms did not escape scrutiny.

In 1957 and 1958 the House of Representatives' Committee on Government Operations investigated claims of 'false and misleading' advertising of filter cigarettes by the big tobacco firms. The Committee concluded that:

The cigarette manufacturers have deceived the American public through their advertising of filter-tip cigarettes.

Without specifically claiming that the filter tip removes the agents alleged to contribute to heart disease or lung cancer, the advertising has emphasized such claims as "clean smoking", "snow white", "pure", "miracle tip", "20,000 filter traps", "gives you more of what you changed to a filter for" and other phrases implying health protection, when actually filter cigarettes produce as much or more nicotine and tar as cigarettes without filters" [6]

Dr Ernst Wynder, who pioneered epidemiological research into smoking and cancer, told the committee that reducing cigarette tar in the smoke by 40% would produce a health benefit. Most filter cigarettes were no better than regular ones, they only provided the illusion of health protection.

The Federal Trade Commission conducted their own consumer research into why people were switching to filters. They found that 40% of their sample changed to filter cigarettes for health reasons and 28% expected a significant health benefit.

The tobacco firms own market research told them the same.

High filtration

Both CU and Readers' Digest continued to find Kent, low in both tar and nicotine. The original Kent was far from the miracle cigarette it promised to be. The mineral used in the Kent filter was crocidolite, one of the deadliest forms of blue asbestos. In 1957 Lorillard replaced the crocidolite filter with a new one made from cellulose acetate. [4]

[Chart 4] Kent sales sky-rocketed after the 1957 Readers' Digest Article, 'The Facts Behind Filter Cigarettes'

In July 1957 Readers' Digest delivered another bombshell to the tobacco industry. Lois Miller and James Monahan exposed the truth about filters in an article called 'The Facts Behind Filter Cigarettes'. They found that Camel was lower in tar than many filter brands and Lucky Strike was lower in nicotine than all apart from two Tareyton and Kent. Smokers had in fact increased their risk of disease by switching to filters, not lowered it as many believed.

Lorillard gave Kent a new cellulose acetate filter in 1957 which outperformed the original asbestos one. It was singled out for praise by Readers' Digest.

The article boosted Kent's sales, perhaps inadvertently. Nevertheless, it encouraged other manufacturers to make filters work by the standards of the day.

Conclusion

Before the big push of filter cigarettes American smokers were giving up. Filters brought few health benefits. They did keep Americans smoking when more might have given up.

By 1960, filter cigarettes, a minority choice in 1950, took over half of the US cigarette market. In 1960, the industry came to a voluntary agreement not to make health claims about filter cigarettes. The Tar Wars were over. But the idea of filters and healthier smoking remained linked in peoples' minds.

Read more:

- Cigarette brands in the 1950s - USA

- Cigarette brands from the 1960s - USA

- Smoking and the 1970s - UK

- 60s cigarette culture - UK

- Vintage cigarette packets - UK

- Players No6 - part of the British scene?

References

[1] 'Cancer by the Carton' by Roy Norr, published in Readers Digest, December 1952, pages 738-739

[2] 'Cigarettes - the industry' published in 'Consumer Reports' by the Consumers' Union (CU) in February 1955, page 63

[3] 'Wanted and available - filter-tips that really filter' by Lois Mattox Miller and James Monahan, published by Reader's Digest in 1958

[4] Unpublished letter to Reader's Digest July 1958

[5] 'TOBACCO: The Controversial Princess' published in Time Magazine, 11 April 1960

[6] 'False and misleading advertising (filter-tip cigarettes), Twentieth Report by the Committee on Government Operations', published in 1958, page 25

By Steven Braggs, August 2011, update May 2021

Comments