Would Marlboro have succeeded without the flip-top box?

In January 1955, the cigarette manufacturer Philip Morris launched a thoroughly revised version of a minor cigarette brand called Marlboro. There was a new advertising campaign, a new tobacco blend, a new filter and a new box.

Philip Morris called the box a 'flip-top' box. It was also known as a crush-proof box, a hard box or a hinged-lid box. It appeared to be a new form of cigarette packaging but the design was twenty years old.

Philip Morris was the first in the world to use the new box. Their market research told them it would be a winner. The following year Philip Morris put other cigarette brands, Spud, Parliament and Philip Morris regular, in the new box. Parliament also sold well in the hard box.

Between 1956 and 1958 other manufacturers scrambled to put their cigarettes in the new box. But the competition did not do well with the new packaging. By 1967 only 6% of cigarette sold in the US were in the new box.

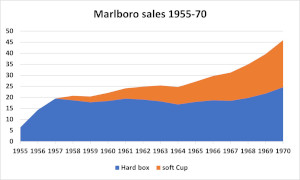

Philip Morris also offered Marlboro in the soft pack, but it sold better in the hard box in almost every year between 1955 and 1990. The box became strongly associated with Marlboro.

In this article I examine how much the hard box contributed to success of Marlboro and Parliament. I will also look at why the hard box failed for other US brands in the 1950s and 1960s.

Background

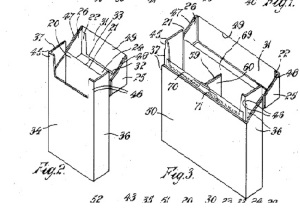

Flip-top box - invention

Philip Morris did not invent the flip-top box. John Walker Chalmers, working for the British company Molins, patented it nearly twenty years earlier. Philip Morris was the first to use it.

Molins was a UK firm which made cigarette manufacturing and packing machines. Without these machines the modern cigarette industry would not have been possible. With these machines cigarette makers turned out cigarettes by the billion at prices people could afford. Molins was one of a small number of firms that sold cigarette making machines worldwide.

The design of the box was critical to how the packing machines worked, so it was natural for experts at firms like Molins to design radically different packaging.

The original design from 1937 showed two types of box. Both held twenty cigarettes. One was double the width of a standard US pack but similar in dimensions to the hull and slide twenty pack familiar in the UK. The other was of similar dimensions to a standard US soft pack.

After Philip Morris other manufactures adopted the box as soon as they could, both in the USA and the rest of the world. In 1956 Player's in the UK used the new pack for their upmarket No 3 blend and Rothmans in Australia used it for King Size plain. Rothmans adopted it in the UK in 1957. The new box became almost standard for cigarettes in the UK and Europe.

The concept and development of Marlboro

Philip Morris' drive for a new cigarette brand came from changes in the cigarette market in the early 1950s. It was the time when the health risk of smoking became a fact rather than a suspicion. The American public read articles in Reader's Digest, Consumer Reports and in the newspapers about the risk of getting their most feared disease, lung cancer, from smoking cigarettes.

The reaction of some was to give up smoking. Giving up was hard, there was only cold turkey in those days. Others managed the risk by smoking fewer cigarettes or smoking what they thought were safer cigarettes. In the early 1950s, 'safer cigarettes' meant cigarettes with a filter.

How much safer? In this article I judge by the standards of the day. People knew little about the reason cigarettes caused lung cancer. They knew less about what in cigarette smoke caused it. There was a feeling that reducing the cigarette tar and nicotine reduced the risk of smoking.

Filter cigarettes filtered out some of the tar and nicotine. So, filter cigarettes when measured in a lab should yield less tar and nicotine than regular cigarettes. But did they?

In 1954, the leading regular cigarette with a reputation as a real man's smoke and How much safera strong tobacco flavor was Camel. It delivered 1.9mg of nicotine and 15mg of tar. Viceroy, the leading filter in that year delivered 2.4mg of nicotine and 13mg of tar. More nicotine and slightly less tar. (Figures from Consumer Reports, December 1954).

The upswing in sales of filter cigarettes was about the perception of safety, not the reality of it. Nevertheless, it was hitting sales of firms that did not have popular filter brands.

Philip Morris found their sales falling off sharply. This was the reason for Marlboro's development.

Philip Morris' project to introduce a new filter brand was pursued with care and skill, using some of the best marketing brains of the era. This effort was important in the ultimate success of the brand.

Philip Morris hired experts from outside the industry. Elmo Roper a marketing research consultant, Frank Gianninoto a graphic designer, Louis Cheskin of the Colour Institute to test the pack for consumer appeal and a new advertising agent, Leo Burnett from Chicago, not one of the Madmen from Madison Avenue, New York.

The whole project was inspired by a report by Elmo Roper back in 1953 into the attitudes of smokers in the USA. Roper found Philip Morris' regular brand was in terminal decline. Not only was it losing sales but the public hated the packaging. They fixed the pack with the help of Louis Cheskin's research. But the need for a filter brand was paramount.

Philip Morris settled on a relaunch of an existing brand, Marlboro, which to that date had been targeted mainly at women smokers. In 1954, new advertising for the old Marlboro featured men and said it was worth paying more for a better cigarette. The campaign, however, did nothing to lift the brand's sales and was an interim measure anyway. All efforts focused on the new Marlboro.

It was essential that the new Marlboro appealed to men. This was to counter the earlier feminine image of the brand but also because many smokers of regular cigarettes thought filters were sissy. Gianninoto with advice from Cheskin used a triangle motive for the pack's graphic design. Cheskin's earlier tests showed the triangle was the shape most appealing to men [1].

They quickly settled on red and white but tried a softer look with thin white lines breaking the red. Burnett claimed he suggested the lines should be go but Giannioto said they had already gone before Burnett joined the project in late November 1954. According to Gianninoto, Burnett's only contribution to the design was to use a capital 'm' for Marlboro; early test packs had a small 'm'.

Another design from Gianninoto had a picture of the cigarette with the filter almost popping out of the pack. Cheskin tested this design against one with a grey Philip Morris crest.

The pack with the Philip Morris crest ranked far higher in association tests. Cheskin's tests showed that customers saw the pack with the cigarette picture as 'ordinary', 'inferior' and 'not for me'. Very few cigarette packs had pictures of cigarettes. Perhaps smokers did not want to be reminded of the contents of the pack.

The pack with the crest rated as 'high class', 'attractive', 'superior' and 'for me'. Heraldic crests were used to give status to cigarette brands all over the world. The other interesting detail was that the pack with the crest only rated slightly more masculine than feminine. [2]

With the pack design almost ready Elmo Roper embarked on a survey to discover if customers preferred the flip-top box to the soft pack.

Roper's associates asked smokers in different locations to try two cartons of the new Marlboro. One had king size cigarettes in soft pack, the other 'long size' cigarettes in a flip-top box. King size cigarettes are 85mm. 'Long size' was 5mm shorter than king size at 80mm. They chose the size so that the pack had the same external dimensions as the traditional soft cup. This was vital for cigarette vending machines but also important for supermarket shelves. Retailers side-lined odd-sized packs.

The study showed a preference off the scale for the flip-top box. Customers thought that the cigarettes in the new boxes tasted better. They were the same, so there was something about the box that made them seem better. [3]

The final part of the strategy was the advertising. At this stage it was not the well-known 'Marlboro Country' ads but did show the beginnings of this strategy.

Leo Burnett's first advert showed a large portrait of a cowboy with the tagline 'The filter doesn't get between you and the flavor'. It certainly did not. In 1956 Consumer Reports found that Marlboro delivered identical tar and nicotine to Philip Morris regular.

The adverting campaign developed to show other men smoking Marlboro. They were working or pursuing hobbies. Some followed overtly masculine activities such as hunting, there were more cowboys, but one man was a chess player. Others wore tuxedos instead of Stetsons.

The common theme of the ads was a tattooed hand. According to Vance Packard, people associated the tattoo with delinquency. [4] Its use in the ad was to show a romantic past. Burnett did not seek out tattooed males, although the models were regular guys not professional models. Artists drew the tattoos with indelible ink. The motive was so popular that Philip Morris was able to distribute millions of transfers so people could stick the Marlboro men's tattoos on their own wrists.

These ads were some of the first to give a brand a personality. Older cigarette ads had shown men and women smoking but these showed a specific group of characters associated with the brand.

Perhaps because of their careful preparation, Philip Morris was behind the competition when they launched Marlboro. It was the third new filter cigarette launched by major tobacco firm between 1953 and 1955. The first was Liggett & Myers' L&M in October 1953. R J Reynolds followed in April 1954 with Winston. Both L&M and Winston outsold Marlboro throughout the decade, as did the older brand, Viceroy launched in 1936. Winston was way out in front clocking up 52 billion cigarettes in 1958, more than twice L&M's total.

But Marlboro had one significant difference to those earlier brands, it's box.

The hard box and other brands

Other manufacturers noticed the success of Marlboro and tried to replicate it. They showed interest in Molins' new packing machines even before Marlboro launched. A Philip Morris board meeting on December 15, 1954 confirmed Molins were putting pressure on them to make an initial tentative order a firm commitment because of interest from the competition.

Philip Morris negotiated an 18-month exclusivity deal with Molins. Other makers had to wait until summer 1956 before bringing out their own hard boxes.

The first to do this was Regent, a small brand owned by Rothmans which brought out the other style of hard box, the double width one, in the fall of 1955. Most likely Philip Morris' agreement did not cover this style of pack. Unlike, Marlboro it was a full king size cigarette, the advert claimed the first in the new pack. Regent was an expensive cigarette with a tiny market share.

The first serious rival to bring out a hard box was Liggett & Myers in the summer of 1956. Others followed as shown below:

- Marlboro (Philip Morris) - January 1955

- Regent fall of 1955

- Parliament (Philip Morris) - 1956

- Spud (Philip Morris) - 1956

- Philip Morris (regular) - 1956

- L&M (Liggett & Myers) - summer of 1956

- Winston (R J Reynolds) - 1957

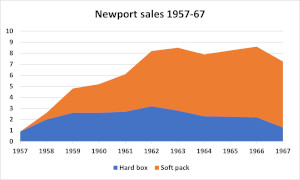

- Newport (hard box only) 1957

- Kent (Lorillard) - 1957

- Viceroy (Brown and Williamson) - 1957

- Oasis (Liggett & Myers) - 1957

- Hit Parade (American Tobacco) - 1957

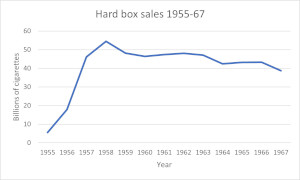

There was some pent-up demand for the hard box, but hard box sales peaked in 1958. The novelty did not last and the hard box did not work well for the other companies.

There are two questions to answer. Why did hard box sales not take off in the US and why did some brands sell better in the hard box than others?

A submarket

The graph shows that hard box sales reached a peak in 1958 and remained static since then with a decline towards the end of the 1960s.

Another motivational research project for Philip Morris found that:

Preferences for a hard pack vs a soft pack for cigarettes are expressed with almost as much vehemence as preference for a particular type of cigarette [5]

This is compelling evidence for a submarket for the hard box.

To understand this further I looked at the percentage of sales in a hard box for a series of brands that adopted the hard box at two specific dates. In 1959, two years after the scramble to introduce hard boxes and ten years later 1967 to show if there was lasting appeal.

The table below shows the percentage of each brands sales that were in a hard box.

| Brand | 1959 | 1967 |

|---|---|---|

| Marlboro | 87% | 59% |

| Parliament | 78% | 47% |

| Newport | 53% | 18% |

| L&M | 14% | 6% |

| Kent | 10% | 5% |

| Winston | 6% | 4% |

| Viceroy | 4% | 0% |

| All filter brands | 16% | 8% |

The table shows that the market for the hard box across all filter brands declined from 16% in 1959 to 8% in 1967. The graph shows a shallower decline because sales of filter cigarettes increased substantially in this period.

The table also shows that the two Philip Morris brands Marlboro and Parliament had a strong affinity with the hard box, Newport had a moderate affinity and other brands had a weak affinity.

The following table shows how strongly Philip Morris brands dominated hard box sales and how Marlboro and Parliament had over 71% of this market.

| Brand | Share of hard box sales (1967) |

|---|---|

| Marlboro | 57% |

| Parliament | 14% |

| Winston | 11% |

| Kent | 6% |

| L&M | 4% |

| Viceroy | 3% |

| Pall Mall | 1% |

Who bought cigarettes in the hard box?

Elmo Roper's 1959 survey found that 31% of smokers claimed they preferred the hard box. For those that did not, they gave these reasons:

- Too bulky - I can't fit in my pocket, purse or case

- Hard to get the cigarettes out of the box

- Cigarettes dry up more quickly in the hard box

- The store does not have it - see remarks above

- I take what the store clerk gives me (hard box or soft pack, I have no preference)

Source: A Study of Attitudes Towards Cigarette Smoking and Different Types of Cigarette' by Elmo Roper dated January 1959

There was also a complaint that you could not tell how many cigarettes were left in the package in the flip-top pack. But most people's reason for preferring the soft cup was the awkwardness of stuffing it into a shirt pocket. The original thought was that you could open the box whilst still in the pocket, no-one really did this. Most disliked the hard edges.

It was men that complained about the bulkiness of the pack. There was a strong preference amongst women smokers for the hard box.

Women find a hard pack cleaner to carry in a handbag since no cigarettes or loose tobacco fall into the handbag. Men on the other hand, find the box too bulky for a shirt pocket. [5]

It was difficult to properly close the soft cup after opening it, so getting loose tobacco in your pocket or handbag was to be expected.

Others moaned about the size of the cigarettes. They were 5mm shorter but sold for the same price. People perceived the soft pack better value.

There was a significant group of smokers who preferred the hard box. These smokers gravitated to brands most associated with the hard box.

Marlboro was the full flavor filter in hard box, Parliament the hi-fi filter in a hard box and Newport the menthol in a hard box.

Marlboro - filter in hard box submarket

To be successful a new cigarette brand had to capture enough of the market to overcome the cost of advertising and marketing.

According to Elmo Roper writing in 1959 the hard box was responsible for most of Marlboro's success. [6] Other commentators also thought that the hard box was a major factor in Marlboro's successful launch.

"The package is primarily credited with a spectacular 5,000% rise in the rate of Marlboro sales in one year." (Cigarettes - Notes on the industry, Cigarette Consumption and Smoking Habits, Market Reports Redbrook Magazine, April 1956, page 17).

Speaking in 1969, Philip Morris President, Ross Millhiser said that the flip-top box "contributed immeasurably to the early success of the brand".

But were the experts right?

The 1954 sales figures for the leading filter bands in billions of cigarettes were:

- Winston - 7.5

- Viceroy - 14.9

- L&M - 7.7

- Kent - 2.5

Estimates by Harry M Wootten published in 1954

Winston was the last of these brands to launch but it had the resources of the second largest tobacco firm behind. It grabbed third place in 1954 and overtook Viceroy to become the leading filter brand in 1955. This was because Brown & Williamson could not meet demand for Viceroy and R J Reynolds was able to plug the gap. Often it was the size of the sales force rather than the imagination of the advertisers or the skill of the designers or tobacco blenders that was the key ingredient.

Philip Morris launched Marlboro into this growing but crowded market in 1955. The odds were against a new brand. Smokers rarely switched brands once they had found one they were happy with.

Philip Morris had the advantage that the filter market was growing but the disadvantage that the leaders were already established. It was difficult to beat an established cigarette brand without outspending it in advertising. Philip Morris spent less than all their competitors. Yet they managed to get Marlboro selling at profitable level, not only that but they exceeded their own expectations and had to increase production.

Was it the pack or another factor that helped Philip Morris to succeed?

Was it the blend of tobacco? Philip Morris were experts at blending. Elmo Roper did a blind test of two 'unknown' brands of cigarette, one was Camel, the most popular brand with reputation for a good blend. The other was Philip Morris' own brand. Most smokers said they preferred the Philip Morris blend. However, since Philip Morris was losing sales at the time, it showed that a good blend was not enough.

The ad campaign was innovative. It was amongst the first cigarette advertising campaigns to successfully create an image for a brand according to motivational expert, Pierre Martineau.[4]

The well-respected advertising agent, David Ogilvy said:

Leo's (Burnett) greatest monument is his campaign for Marlboro. It made an obscure brand the biggest-selling cigarette in the world.

'Ogilvy on Advertising' by David Oglivy, published by Pan Books in 1983, page 201

Robert Glatzer in 'New Advertising : 21 Successful Campaigns from Avis to Volkswagen' (1970), called it 'the campaign of the century'.

Of course, Ogilvy and Glatzer were referring to whole Marlboro campaign from 1955 at least until 1970. Its recognizable and most effective form was with cowboys in every ad and the tagline 'Come to where the flavor is, Come to Marlboro country'. But this did not start until 1964. Before then sales had plateaued. They rose strongly after 1965 which was around the time the new ads would have penetrated.

Even in its embryonic form the Marlboro campaign received praise from within the industry. Cameron Day, writing in 'Printers Ink' in 1956 said that:

"The large, striking illustrations, plus the agile alliteration (filter, flavor, flip-top box) seem to be building steadily with smokers"Not quite the campaign of the century. The competition also took note of the early ads and imitated the style. Was this enough with only a modest budget?

What about the box? According to Ira Taylor in 'Brand Performance in the Cigarette Industry 1913-74', it was key to be first with a new idea. As a filter cigarette, Marlboro trailed Viceroy (Brown & Williamson), L&M (Liggett & Myers) and most importantly Winston (R J Reynolds). Later entrants had to adopt other tactics to succeed:

later entrants may be forced either to differentiate their products, thereby becoming the first entrant in a new submarket, or to "reach" a segment of potential customers which has not been tapped by the first entrant.

'Brand Performance in the Cigarette Industry 1913-74' by Ira Taylor, page 5

The new box was a clear differentiator.

The new box and the ads together started to build a brand. There were contradictory elements. The box was modern, the ads slightly backward looking. The characters in the ads were working men. The brand name came from Marlborough Street in London, Philip Morris' original headquarters, so posh. Taken together they were the anatomy of a successful brand; several disparate elements brought together as if by chance but in fact carefully planned.

But the packaging was the principal factor. According to an unnamed survey done for American Tobacco in 1959:

It is easy, in retrospect, to exaggerate the importance of this brand image to the success of a product which primarily exploited a new and unique packing.

The selling factor of the pack's design was further strengthened by the poor design of the competition. The public disliked the Winston pack. Elmo Roper found it rated fifth behind Chesterfield, Pall Mall, Lucky Strike and Philip Morris (regular).

Appreciation of package design was particularly strong in urban areas. The hard box was popular in New York. Marlboro's sales there almost matched Winston's.

The care Philip Morris paid to the packaging was shown by subtle changes they made to the original design. When Philip Morris improved the filter in late 1957, they changed the crest from grey to gold. This serves as a recognition point for collectors looking for the first version.

The graph shows the strong affinity of Marlboro with the hard box and the static nature of the hard box as a submarket. It also shows how key the hard box was to Marlboro's early success. Had they launched first in the soft cup and L&M been first with the hard box, these sales would have gone to L&M. Marlboro may well have failed, despite Leo Burnett's advertising.

In the 1950s, Marlboro smokers strongly preferred the box to the soft cup. In a later survey, Elmo Roper found little enthusiasm for a soft pack amongst Marlboro smokers. But he did find that offering a soft cup alongside it could attract sales from other brands. This was a warning that the flip-top box was not going to live up to Roper's original expectations.

Elmo Roper thought that the flip-top box was key to Marlboro's original success but by 1959 it was a disadvantage that brand was so associated with this type of packaging. Marlboro was the 'one the hard box'.

Once the soft pack launched Marlboro adverts favored it over the flip-top box, often showing only the soft pack in the ad. Most of the new sales in Marlboro's strong period of growth were in the soft pack but Marlboro still sold better in the flip-top box.

Hit Parade

American Tobacco was the largest tobacco firm in the USA. They had far more resources than Philip Morris. American launched another new filter cigarette, Hit Parade in October 1956.

The name came from the TV show, 'Your Hit Parade', which American sponsored through Lucky Strike.

Whilst Hit Parade came after Marlboro, American's resources should have given them every chance of success. Nevertheless, Hit Parade flopped.

There were reasons for this. Hit Parade's red and white pack was not well designed. The brand name lacked subtly and looked like a shameless pitch to the youth market. This was a bad choice. Teenagers probably saw through the pitch and older smokers did not like the idea of young people smoking, so probably hated the brand. People also complained they did not like the taste. However, this may have been more to do with their perception of the brand as a dud.

Significantly Hit Parade did not come in a hard box at first, although American soon added one and it made no difference to the brand's prospects.

Newport - menthol filter submarket

Another example is P Lorillard's Newport. Newport was a menthol (flavored) cigarette. Menthols were also seeing robust growth in the 1950s. Customers saw them as almost medicinal. In fact, they were no better than other cigarettes. Newport was in a new sector combining menthol with a filter. Like Marlboro it lagged a strong competitor, Salem, also by R J Reynolds.

Newport was not the first menthol to use a hard box. Philip Morris owned the Spud brand, the first ever menthol cigarette, to which they added a filter and a hard box in 1956. It did not get the same careful marketing as Marlboro. Philip Morris did not run enough adverts and probably the name was wrong.

Like Marlboro's box Newport's was well-designed. The brand name was also a good one with upmarket overtones.

Like Marlboro, Newport established a niche selling nearly 5 billion units by 1959. However, that is not the whole story as Lorillard quickly added a soft pack, which eclipsed the hard box in sales.

It is strange that Newport did not achieve the same affinity with the hard box as Marlboro. This is especially odd because women preferred both menthol cigarettes and a hard box. It is possible that the short interval between the launch of Newport in the hard box and Newport in the soft cup had some influence on this.

Launched in the same year as Newport, Liggett & Myers' menthol cigarette, Oasis, started in soft pack. They added a hard box later. Oasis was a complete flop. The hard box helped Newport become successful, although it ultimately did not have the same affinity with the box as Marlboro.

Parliament - high filtration submarket

Another submarket example is Parliament. Philip Morris bought Parliament when the company merged with Benson & Hedges in 1953. They relaunched the Parliament brand in 1956 with the help of Louis Cheskin's research. It got a new flip-top box with a chevron motive and a dark blue colour scheme. They priced Parliament at 1-2c higher than the popular filters such as Marlboro. It was a little bit upmarket.

But Parliaments main success came after Readers' Digest published an article calling out the lie in filter cigarettes in 1957. They claimed that only Kent had a filter worth mentioning. The rest were useless, or worse than useless. This was a game-changer for the tobacco industry and shook-up sales again yet again. Philip Morris responded by re-engineering Parliament to be 'hi fi' (high filtration) Parliament to compete with Kent. They took advantage of Parliament's history with a hard box to carve out a niche as a high filtration cigarette in a hard box. Although Kent was also available in the hard box by then, it was less well distributed in that form of packaging. Parliament still outsold Kent in a hard box by more than double even in 1967. It would have probably disappeared without the hard box.

The hard box was a significant element in the success of Parliament, Newport and Marlboro. Probably none would have succeeded without it. It was not a substitute for advertising or distribution but allowed late entrants to get a foothold. Marketing power and financial resources, on the other hand, could succeed with a bad pack as Winston proved.

Why did only a few brands succeed with the hard box?

Being first was important to success in any market. Industry insiders understood this in the 1950s. Those most successful with the hard box were the first to launch with it in their section of the cigarette market. They had a huge advantage. But why was it so important?

- Identification - smokers often identified a particular brand with a particular feature

- Availability - it was difficult to find some brands in the hard box, although it was available somewhere

- Familiarity - if a brand first came out in a soft pack, smokers were reluctant to change and vice versa

- Philip Morris' trademark registration of the name 'Flip-top box'

Identification

Smokers identified a particular brand with a particular attribute and were often not aware of other brands. Often it was the first brand to have that attribute.

According to the Market Planning Corporation in a report for Liggett & Myers in 1957 both Kool, the first menthol cigarette, and Pall Mall, the first king size had a huge advantage in their sectors:

Kool is an old established brand, it is the mentholated cigarette for many. ... and a number of people do not realise that there are other mentholated cigarettes.

The advantage that Pall Mall gained from being the the first king size cigarette on the market cannot be under-estimated. Many respondents are "psychologically blind" to other king size cigarettes.

Brands which were the first to use the hard box in their market sectors had this same advantage.

Availability

All the stores did not stock all the brands in all the packs. The number of brands mushroomed in the mid to late 1950s. As well as brands there were variants of brands: king size versions and filter versions of the same brands. Retailers could not carry every brand and ever sub-brand, so chose the most popular of each one. If soft cups came first, some only stocked the soft cup. If a customer wanted Winston in a hard box, they might have to settle for Winston in as soft pack.

This was particularly true for vending machine sales which made up 16% of cigarette sales in the 1950s. Standard cigarette vending machines had ten columns, so sold ten different cigarette brands. Newer machines, from the mid-1950s took twenty different brands. But this was not enough to cover all variants. According to Elmo Roper in 1950, stocking just six cigarette brands would cover 90% of the market but by 1956 you would need seventeen. But if you wanted a hard box and soft cup version of every brand, there would not be enough columns.

Since Marlboro, Parliament and Newport were first launched in the hard box retailers may have been reluctant to stock the soft pack. Especially if good sales were already established in the hard box. The reverse was also true for brands first launched in the soft pack.

How long companies waited before introducing the second package type mattered. Newport launched in the soft cup only 9 months after the hard box, when the brand was in its infancy. This was responsible for its weaker affinity with the hard box. Parliament and Marlboro launched in the soft cup up to three years after the hard box. Other brands were on the market for three years or more before the hard box came along. They had built up sales in the soft cup.

Availability also had an impact on Winston hard box sales. Although, most Winston sales were in the soft cup, it was the third most popular cigarette in a hard box in 1967. This is almost certainly because Winston was so well distributed being America's most popular cigarette at the time. It was easier for retailers to stock Winston in both forms of packaging.

Familiarity

Smokers often tried different brands but once they found one they liked they stuck with it. Many tried the new filter brands and if they decided they liked filter cigarettes chose a brand that they liked. Since Marlboro was first as a full-flavor (or ineffective) filter in a flip-top box, smokers who liked the box had already made their choice before the others came out. This coupled with the likely unavailability in of the other brands in this packaging helped seal Marlboro as the cigarette in the hard box.

Trademark

The phrase 'flip-top box', which was unique to Philip Morris. They had registered it as a trademark. Other makers had to use different, less catchy, terms:

- Viceroy - "flip-open box"

- L&M, Winston, Kent, Newport - "crush proof box"

This may have had a small effect as other makers could not use 'flip-top box' in their ads.

Conclusion

The reason for Marlboro's early success against the odds was that the hard box created a submarket of smokers who preferred it to the soft cup.

However, the appeal of the box was limited. Demand for the hard box remained static throughout the 1960s. Brands that had a strong affinity with the box had most hard box sales. Other brands sold only a small percentage in the hard box. The brands that had the strongest affinity were those that launched only in the hard box with a significant delay before the soft pack was introduced.

The hard box was responsible for Marlboro becoming a profitable brand in the 1950s, its ultimate success was down to Leo Burnett's advertising campaign from 1964 onwards.

Cigarette packaging was a factor in boasting sales in the 1950s, but it was not the most important one. Cigarettes still sold in bad packaging if other factors were right. But good packaging could help some brands to carve out a niche.

References

[1] 'Secrets of Marketing Success' by Louis Cheskin, published by Trident Press in 1967, page 136

[2] 'Secrets of Marketing Success' by Louis Cheskin, published by Trident Press in 1967, page 237

[3] 'A Consumer Test of Three Marlboro Filter Tip cigarettes' by Elmo Roper dated November 1954

[4] 'The Hidden Persuaders' by Vance Packard, published by David MacKay in 1957, page 85

[5] 'Smoking behavior and smoker motivation - their implications for packaging', Opinion Research Corporation, December 1961, for Philip Morris

[6] 'A Study of Attitudes Towards Cigarette Smoking and Different Types of Cigarette' by Elmo Roper dated January 1959

By Steven Braggs, January 2024, updated February 2024